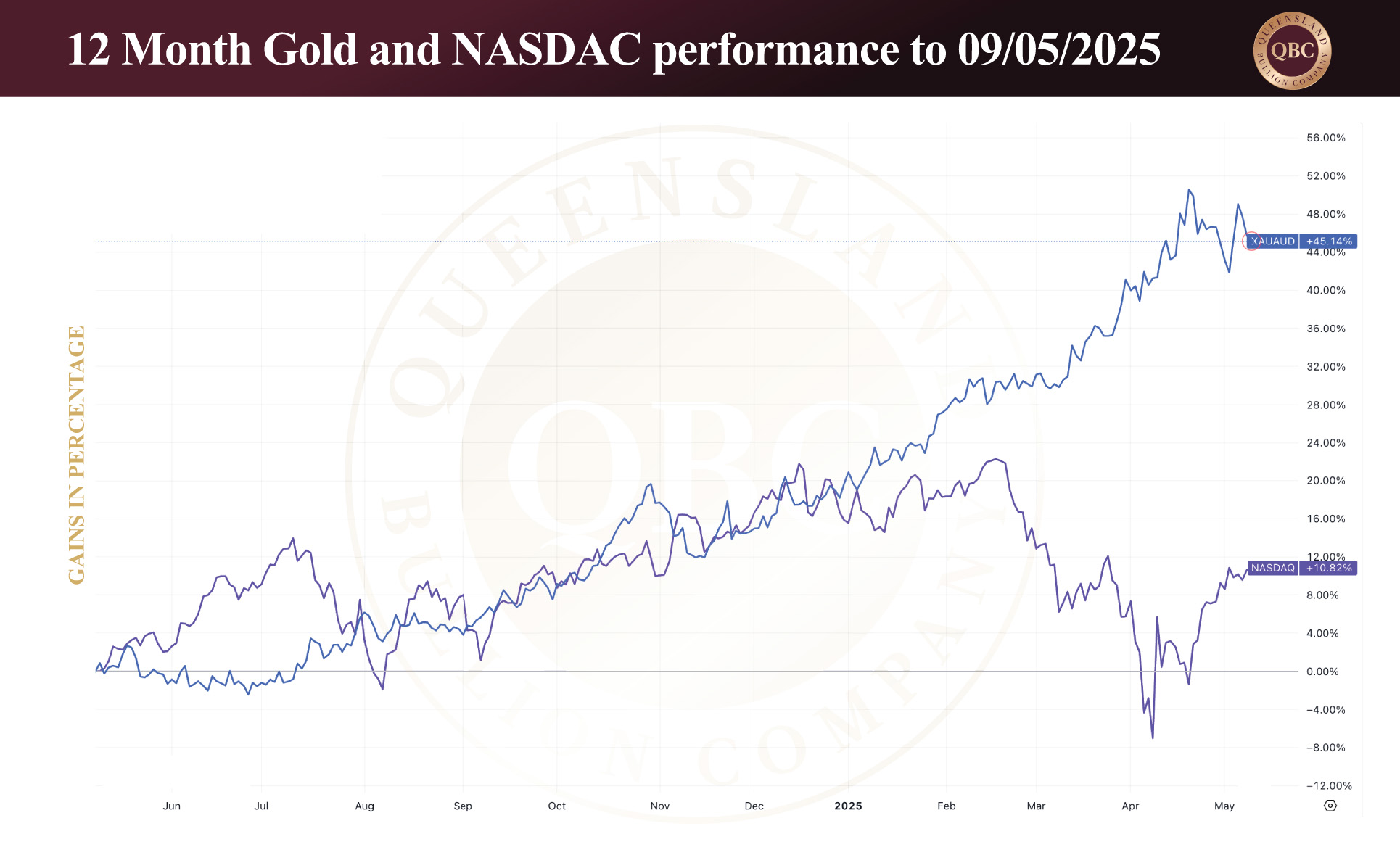

High bond yields are currently a hot topic as 20-year US Treasury bonds peaking over 5% yields last week. With gold trading at AUD $5,154.73, silver at AUD $51.89, and platinum at AUD $1,680.62, it is a good time to pause and consider the wider implications of the international bond market—and how it could be the source of the black swan that astute investors is monitoring closely.

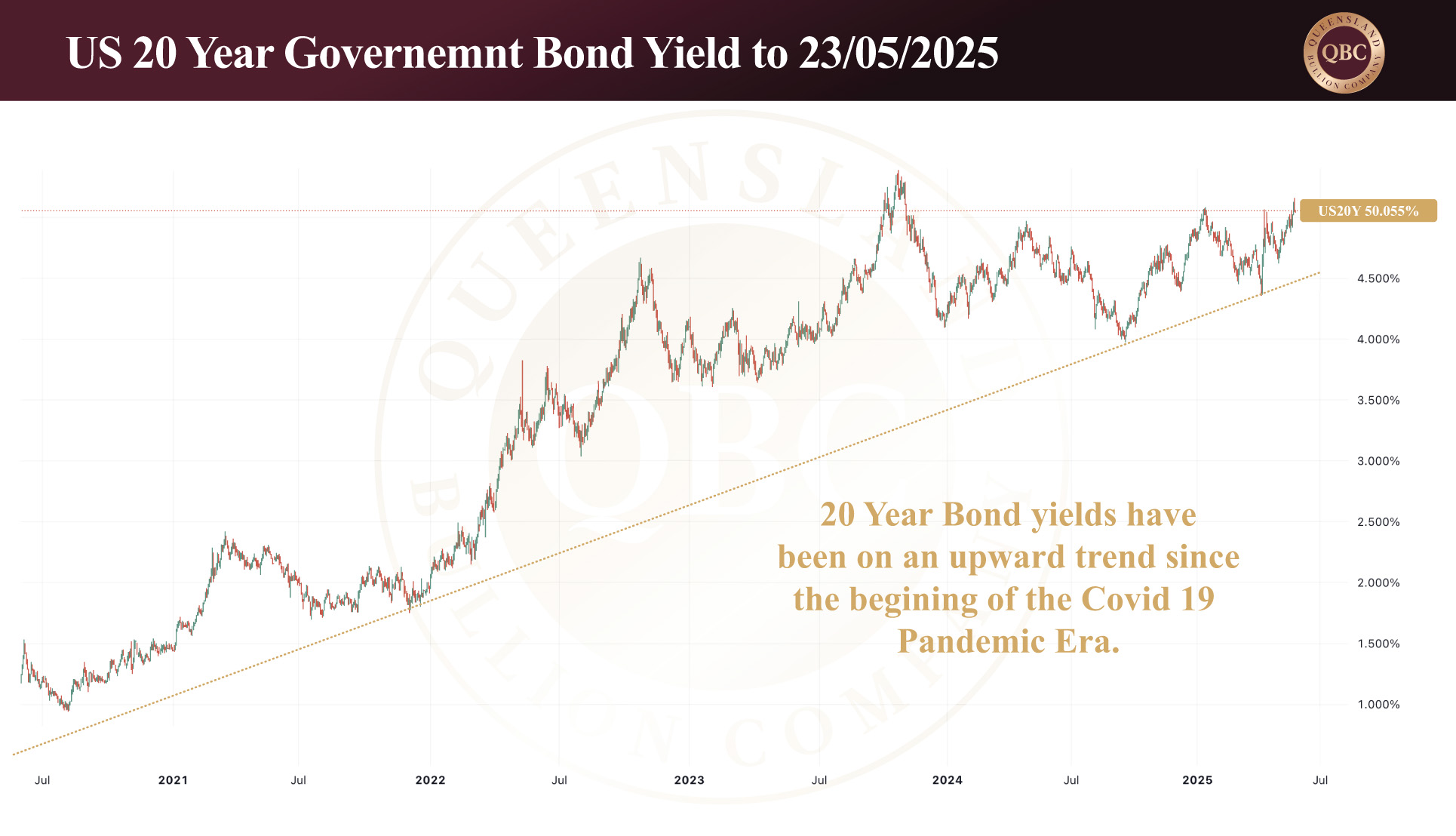

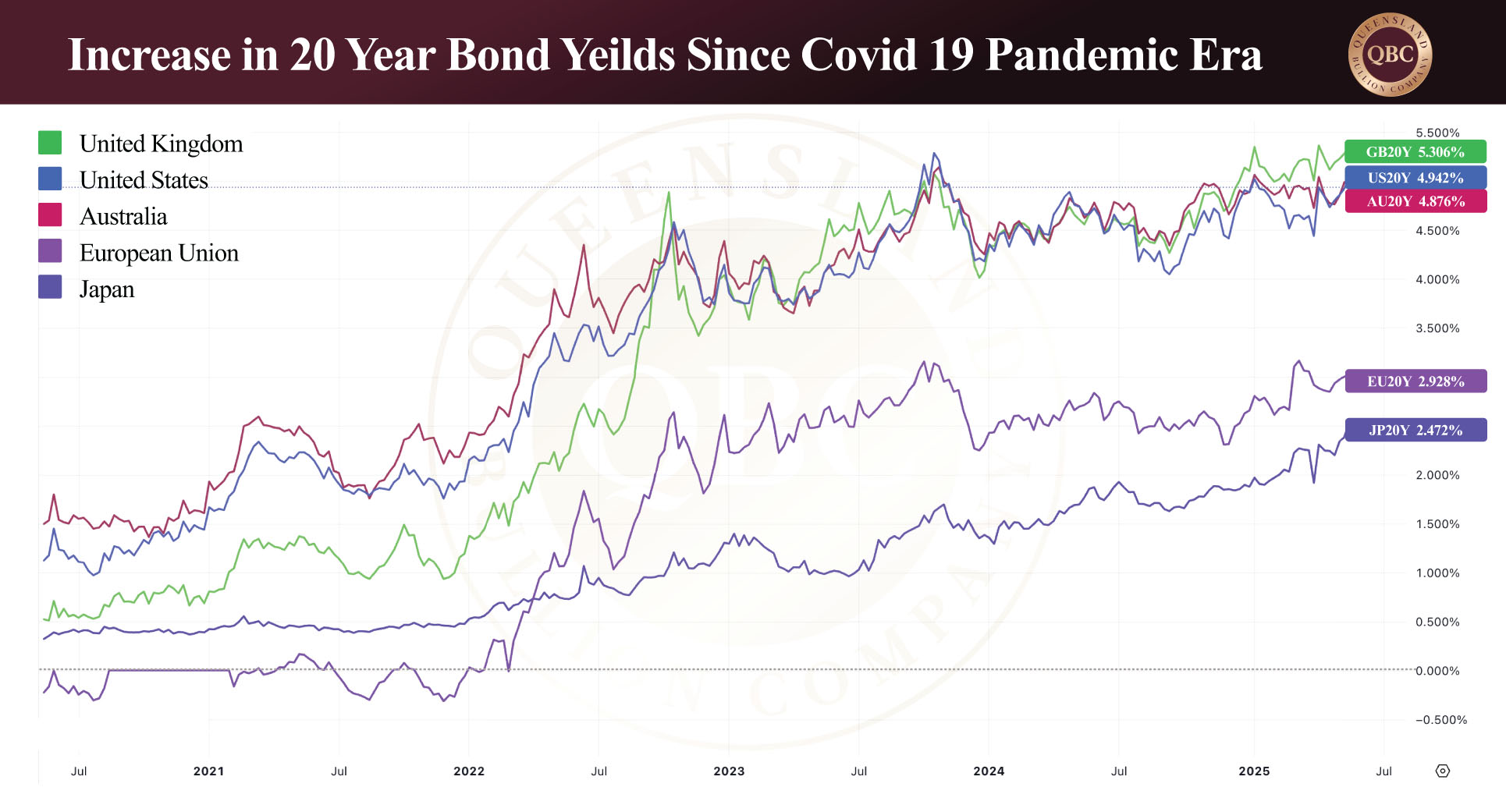

This article builds on last week’s discussion regarding bonds and margin calls. Find the full article here to follow the thread. To briefly recap: we explored how rising interest rates on US Treasury bonds (yields) indicate a lack of confidence in the government’s ability to repay debt, and how that concern eventually transfers to the private sector—specifically equity shareholders (investors in the stock market). Stepping back to view the bond market in the context of the international financial landscape, the picture becomes somewhat more alarming. Since the start of the Covid-19 Pandemic Era, bond yields have risen significantly—a marked indicator of how the market assesses the fragility of what is considered one of the safest assets in the world.

The graph below of 20-year government bond yields illustrates how the United States, Australia, and the United Kingdom have all had to increase returns significantly in order to attract investors to purchase government debt. This is an understated admission of risk being factored into doing business with governments that have, historically and perhaps technically, never defaulted—yet. What this graph shows is that lack of confidence is not limited to the United States; it is global, and rightly so.

Japan

Note on the graph that Japan fares the best. At first glance, this may appear to suggest sound financial management and investor confidence. But it is not, and here is why.

Japan’s debt-to-GDP ratio is one of the highest among developed nations, sitting at 263% and equating to USD $8.84 trillion (AUD $13.35 trillion). This is largely because approximately 38% of their population is over the age of 60. While this may imply wisdom, it also means Japan’s workforce has been in long-term decline. For governments, a large senior population and a shrinking working base means greater capital expenses and reduced collectable tax income. Japan has managed this by keeping interest rates at or near zero to attract investor capital.

Enter the yen carry trade

The yen carry trade is a financial strategy involving borrowing in Japanese yen at extremely low interest rates and using those funds to invest in higher-yielding assets abroad. For example, investors borrow yen, convert to USD, and purchase US Treasury bonds. Japan offers near-zero borrowing costs, while the United States offers high returns and an ironclad repayment history (including the ability to print money if required).

The problem arises when Japan’s bond yields begin to rise, signalling an increase in the Bank of Japan’s (BOJ) interest rates. Since 2016, BOJ maintained a negative rate of –0.1%, until 2024, when it began lifting rates to the current level of 0.5%. While still low by international standards, this has required major adjustments from investors using the yen carry trade.

Wouldn’t the higher yields from US bonds offset Japan’s rate hikes? In isolation, yes. But the complication comes from foreign exchange pressure: as Japanese interest rates rise, so does the strength of the yen relative to the US dollar. Investors who borrowed in yen now need more USD to repay their loans. This currency cost, combined with higher interest expenses, is forcing many to unwind their positions.

Yen carry trade: cause and effect

Japanese institutional investors (including banks, pension funds, insurers, and investment trusts) are the largest foreign holders of US Treasury bonds. They currently hold USD $1.13 trillion (AUD $1.71 trillion) in US debt. As the yen carry trade unwinds, the American government may have just lost its most important customer.

At the same time, the US Treasury just last night received USD $17.869 billion (AUD $26.96 billion) in offers to sell back bonds before maturity. Only USD $2 billion (AUD $3.02 billion) was accepted. This speaks volumes about the financial strain now facing the US government. If Japanese investors were not only to stop buying but to begin selling their Treasury holdings into the same market the US Treasury is attempting to sell into, it could spell pandemonium. A black swan event beginning in the bond market is no longer difficult to imagine.

What does this mean for gold?

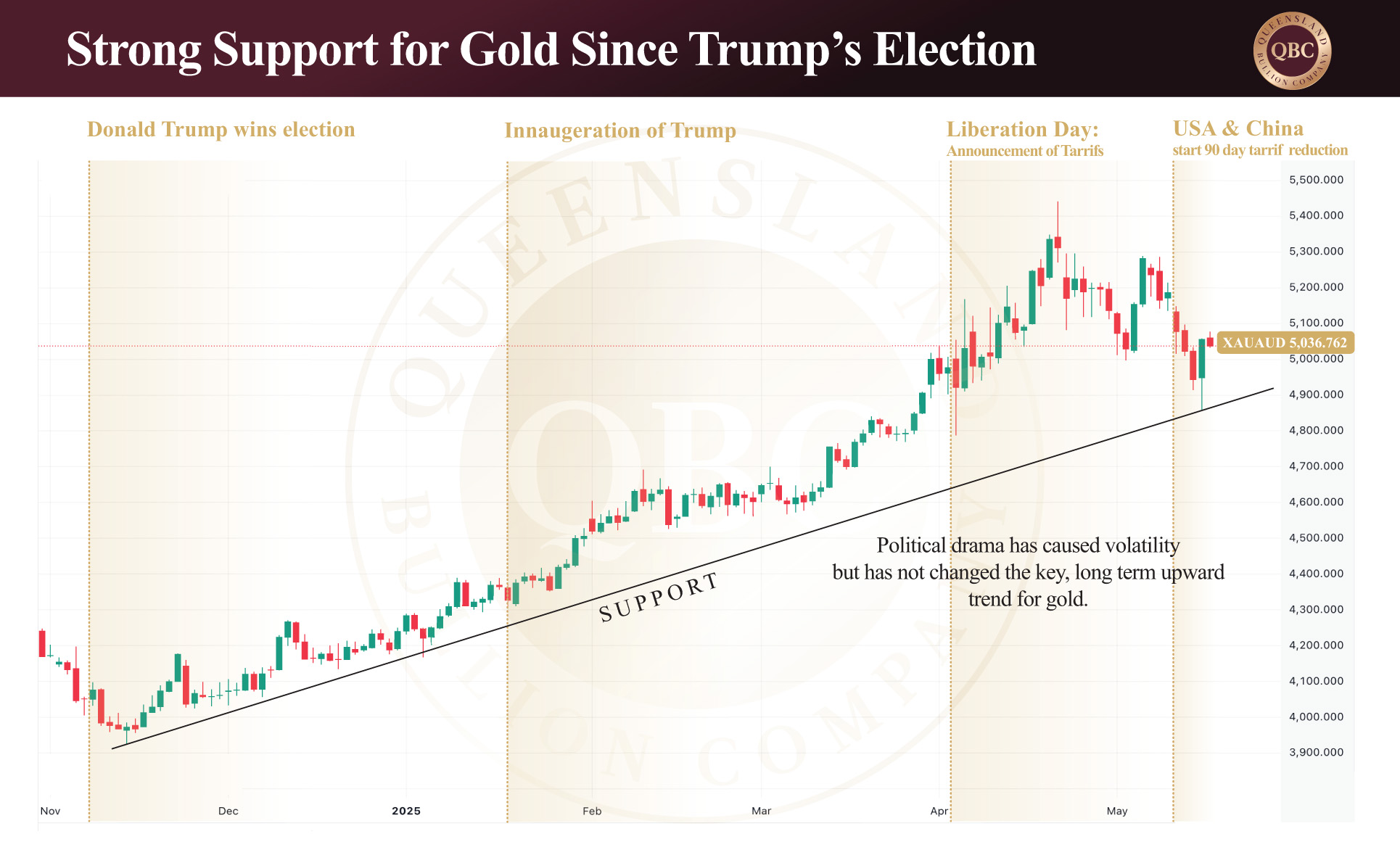

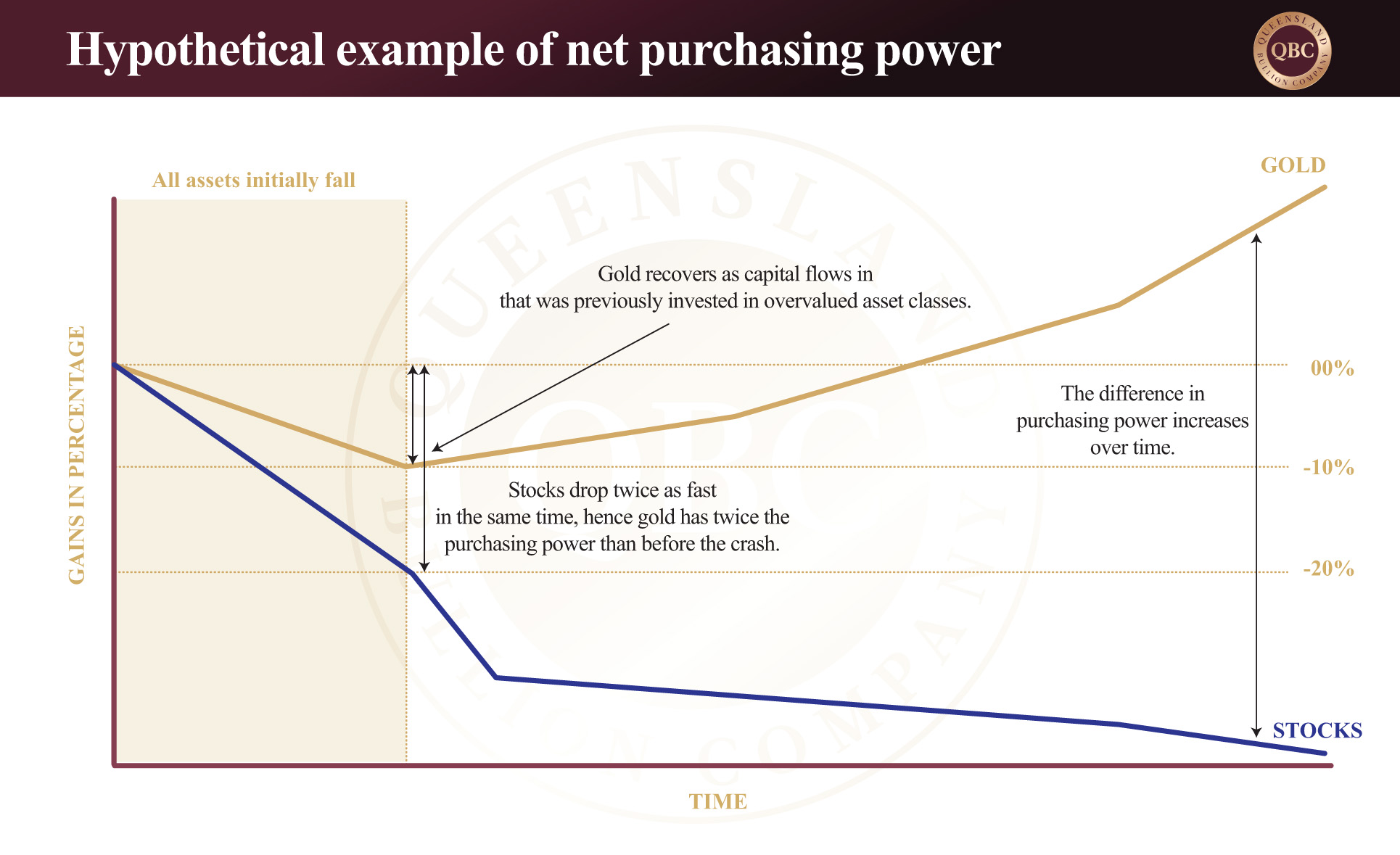

As mentioned in our previous article, there are two ways this could unfold for gold. If bond yields continue to rise due to declining market confidence, bonds will dominate investor attention as a source of yield. In that scenario, gold may soften.

However, in a more probable and far-reaching scenario, bond markets around the world may destabilise. If that happens, gold is likely to surge as risk-averse capital floods into the precious metals sector. The real question is timing—something even the best among us cannot predict.