Is Cash in the Bank High Risk? Bank Bail-In Laws

by Evie SoemardiGold finished strongly for the week. After early resistance near AUD $5,150, it pushed above $5,200, and currently trades at $5,189. Silver, on the other hand, saw a more volatile $2 trading range before reaching higher and is at $59.53. Platinum, at $2101, remained steady largely moving sideways. Precious metals continue to benefit from uncertainty in global financial systems, with one issue coming into sharper focus as we edge closer to a major correction: Australian bank bail-in laws. These laws, introduced in 2018, could directly impact those holding cash deposits, and highlight why gold, silver, and platinum remain critical stores of value outside of the banking system. Passed by the Senate on Valentine’s Day, the laws are less of a love letter to Australian bank depositors and more like a tightly sealed pre-nuptial agreement that you probably never read before investing in the relationship.

Australia’s bail-in laws

In 2018, amendments to the Banking Act 1959 via the Financial Sector Legislation Amendment (Crisis Resolution Powers and Other Measures) Act brought Australia in line with the Bank for International Settlements’ (BIS) global “bail-in” framework, agreed at the 2014 Brisbane G20. Unlike the 2008 bail-outs that used taxpayer money to rescue failing banks, bail-ins place the burden on a bank’s creditors which, crucially, can include depositors.

Under the law, APRA (the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority) has “crisis powers” to step in, run distressed banks, and convert certain securities or deposits into capital to stabilise the institution. SMSF cash holdings are explicitly exposed, while ordinary deposit accounts are not excluded, which opens them to the possibility that they also could be written down or confiscated in a crisis. Rather than curbing risky investment behaviour by banks, the framework prioritises repayment of banks’ derivatives obligations ahead of depositors, raising concerns that everyday savers could be sacrificed to protect interbank exposures.

Bail-in versus bail-out

A bail-out involves taxpayer-funded capital injections, as seen during the Global Financial Crisis when governments rescued banks in the U.S. and Europe. Australia has historically avoided direct bail-outs, though during 2008–09 it guaranteed deposits and wholesale funding to protect stability. Bail-ins, by contrast, recapitalise failing banks by forcing creditors (including bondholders, hybrid investors, and potentially depositors) to absorb losses. This reduces taxpayer exposure but shifts risk squarely onto the private sector, potentially including those with cash in the banks. By passing bail-in laws, Australia is just one of the G20 countries positioned to prioritise banks over people by legally being able to confiscate cash deposits in banks.

Who are the creditors that bail-in applies to?

In essence, when you deposit money into a bank account you lend that money to the bank. This is why they pay you interest. The banks then use your money to fund other projects, all of which allow them to produce a profit. They do this under a fractional reserve system and retain only a small portion as liquid reserves. You hold the right to demand payment which is what happens when you withdraw your money from the bank. But until you withdraw it they loan it from you. Because you lend your money to the bank, you hold the status of unsecured creditor. And as a creditor, you could be subject to bail-in laws. Under bail-in law, your right to claim payment can be written down if a bank is in distress, putting depositor funds at risk.

The $250,000 deposit guarantee is not absolute

People are generally more aware of Australia’s Financial Claims Scheme (FCS) than bail-in laws. The FCS may provide a government guarantee of up to AUD $250,000 per account holder, per authorised deposit-taking institution (ADI). Falling back on the FCS is often the first response from people on learning of the bail-in laws in an effort to dismiss risk.

However, this protection has limits:

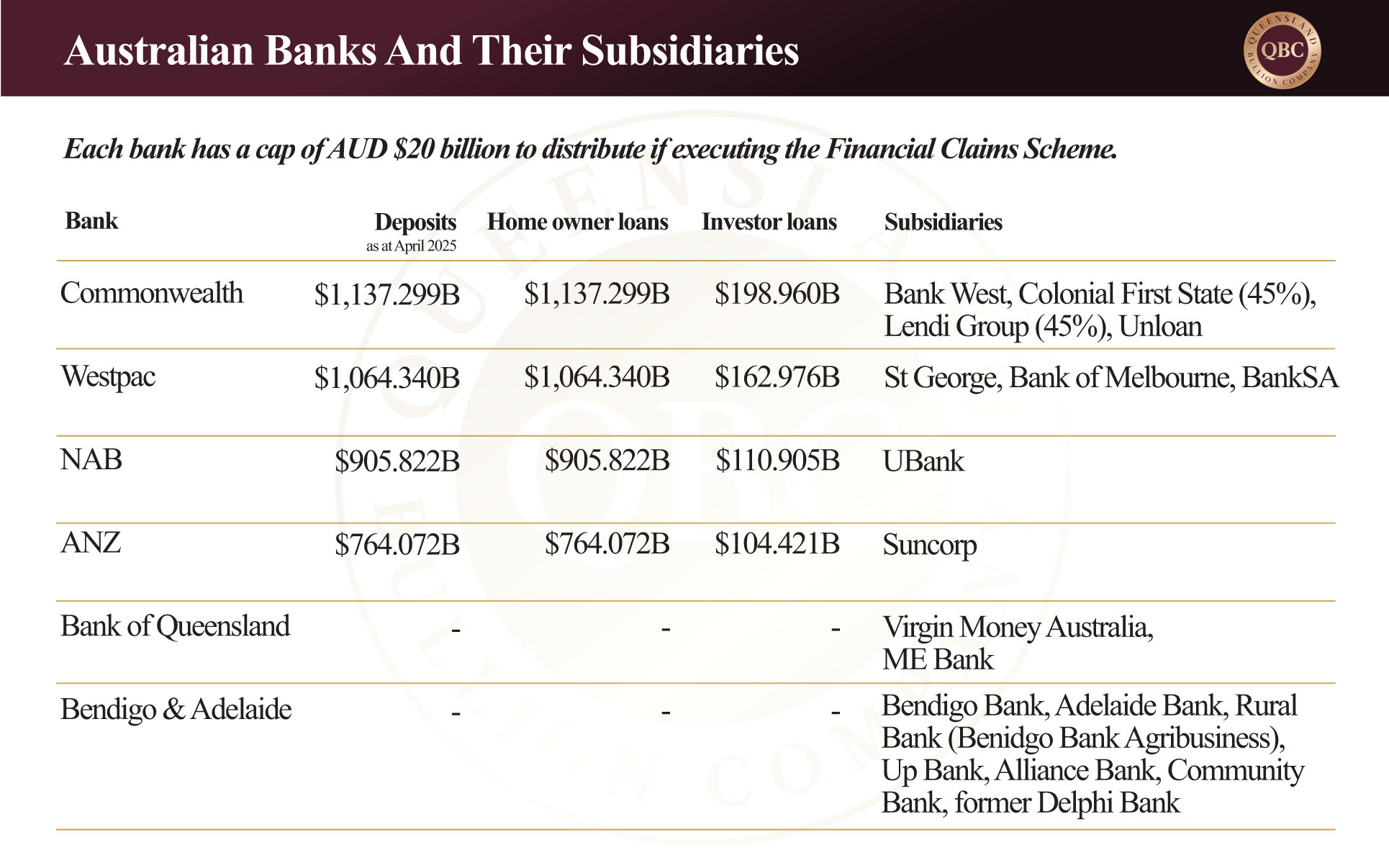

Multiple banks under a single licence are treated as one entity. This means that if a person’s wealth is spread across two entities that share a licence, the guarantee is split between them. For example if an individual has $50,000 deposited with St George, another $200,000 with Bank of Melbourne, and $300,000 with Westpac, they are only guaranteed a total of $250,000 across all accounts because these banks all use the same licence. They could lose at least $300,000 (if not more) should the FCS ever be activated to “protect” their financial assets.

The $20 billion cap per ADI may be insufficient for large institutions. Refer to the table below and consider how far this will stretch across each bank and their deposits, and subsidiaries.

Critically, bail-in powers are applied before the FCS is triggered, meaning depositor funds could be used to stabilise the bank first. And only if the bank fails outright would the FCS potentially provide reimbursement.

Due process guarantees a delayed payment. FCS are to be paid out “within seven days.” However, this starts after APRA’s attempt to first rescue the failing institution (by implementing bail-in), then they must apply to the Treasurer for support to declare the institution insolvent. This process must go through the courts, then FCS is implemented, and you get the remainder of your money after bail-in “within seven days.”

Why this matters for investors

The IMF has noted that bail-in laws indemnify bank executives from liability, further shielding institutions and reducing accountability. This framework makes clear that in a crisis, depositor protection is not absolute. Holding significant cash in banks exposes savers to the risk of their funds being used to rescue the very institutions meant to safeguard them.

With bail-in laws enshrined in Australia, cash in the bank is not risk-free. Depositors are legally creditors and their funds could be at risk should a bank faces distress. This reinforces the case for precious metals as a decentralised, tangible store of wealth that sits outside the banking system. Gold, silver, and platinum cannot be “bailed in,” written down, or subjected to derivative losses. At a time when global monetary policy and financial stability are under strain, bullion offers investors independence and protection that bank deposits simply cannot guarantee. Those savvy with their wealth understand what Shakespeare meant when he penned “it is better to be three hours early than one minute late.” Preparation with a layered defence before a financial correction allows time for unexpected delays, avoids panic, reduces stress, and provides stability and strategy for the investor and consequently their dependents. There has never been a better reason to invest in gold and silver today.